On

December 15, 1802 at 9 in the night he was born in Kolozsvár (today Cluj).

His native house at the corner of Tivoli Street and Belső Közép Street (later

Deák Ferenc Street, today Hősök Avenue / Bld. Eroilor) has been marked with a

memorial plaque since 1903.

On

December 15, 1802 at 9 in the night he was born in Kolozsvár (today Cluj).

His native house at the corner of Tivoli Street and Belső Közép Street (later

Deák Ferenc Street, today Hősök Avenue / Bld. Eroilor) has been marked with a

memorial plaque since 1903.

His genealogical tree is more or less known from the 13th

century on. According to family traditions, the Bolyais were landowners of

importance between the 14th and 16th centuries. A number of them have been

remembered as brave soldiers, but not all of them had a fortunate life. One

Gáspár Bolyai was executed in captivity by the voivod of Wallachia in 1599, and

one János Bolyai spent ten years in Turkish prison in the first half of the 17th

century.

His genealogical tree is more or less known from the 13th

century on. According to family traditions, the Bolyais were landowners of

importance between the 14th and 16th centuries. A number of them have been

remembered as brave soldiers, but not all of them had a fortunate life. One

Gáspár Bolyai was executed in captivity by the voivod of Wallachia in 1599, and

one János Bolyai spent ten years in Turkish prison in the first half of the 17th

century.

Beginning with the 17th century the family gradually

impoverished, and even the Bolyai castle fell in the hand of strangers. The

grandfather of János, Gáspár Bolyai only had a small estate near to the village

of Bolya, which was complemented by the heritage of his wife Krisztina Pávai

Vajna, another estate near to Domáld in the county of Kis-Küküllő.

Beginning with the 17th century the family gradually

impoverished, and even the Bolyai castle fell in the hand of strangers. The

grandfather of János, Gáspár Bolyai only had a small estate near to the village

of Bolya, which was complemented by the heritage of his wife Krisztina Pávai

Vajna, another estate near to Domáld in the county of Kis-Küküllő.

His father, the mathematician, writer and educationalist Farkas

Bolyai (1775–1856), corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

(1832) held his inaugural speech on May 4, 184 in the Calvinist College of

Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureş), where he taught mathematics, physics and chemistry

between 1840 and 1851. He was also concerned in playwriting, translating,

medicine, music, painting, forestry,

and

he also took up the planning and producing of energy-saving chimneys. His main

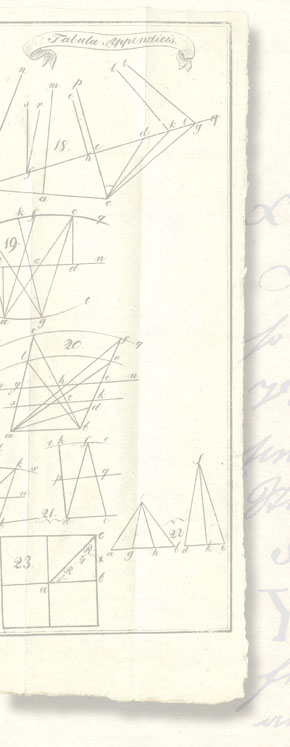

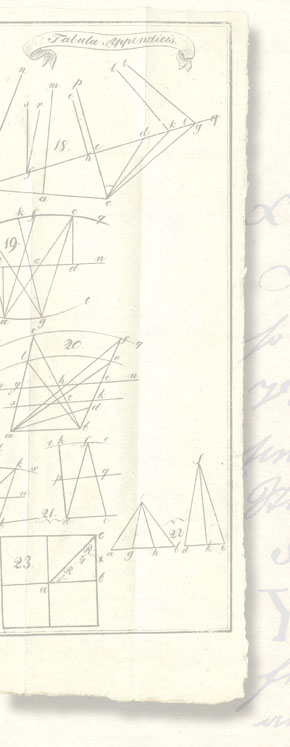

work is the mathematical Tentamen whose

first volume was published in 1832, the second in 1833. His mathematical oeuvre

focused on the attempt to demonstrate the 5th postulate of Euclid. It was later

his son János to point out that the 5th postulate could not be demonstrated from

the rest of the axioms of Euclid. The research of Farkas Bolyai is nevertheless

very important because of his recastings of the postulate. He also made

remarkable achievements in the research of the theory of sets, the convergence

of infinite series and the finite equivalences of territories. János’ mother, Zsuzsanna Benkő of Árkos (between 1778 and 1780

[?] - 1821) was the ninth, youngest son of the surgeon József Benkő and Julianna

Bachmann. In February 1805 was born Anna, the sister of János, who

died before December 18, 1807.

and

he also took up the planning and producing of energy-saving chimneys. His main

work is the mathematical Tentamen whose

first volume was published in 1832, the second in 1833. His mathematical oeuvre

focused on the attempt to demonstrate the 5th postulate of Euclid. It was later

his son János to point out that the 5th postulate could not be demonstrated from

the rest of the axioms of Euclid. The research of Farkas Bolyai is nevertheless

very important because of his recastings of the postulate. He also made

remarkable achievements in the research of the theory of sets, the convergence

of infinite series and the finite equivalences of territories. János’ mother, Zsuzsanna Benkő of Árkos (between 1778 and 1780

[?] - 1821) was the ninth, youngest son of the surgeon József Benkő and Julianna

Bachmann. In February 1805 was born Anna, the sister of János, who

died before December 18, 1807.

Between 1806–1814: János at the age of five already knew several stars, and could draw some constellations by memory. At the age of six he started to read almost by himself. One year later he began to learn to play on violin, and at the same time he started to learn German. He began his regular studies at the age of nine, but his father at this time did not send him to the College yet, but the senior students came to their home to teach him. In mathematics he was instructed by his father.

In 1814 János became an ordinary student of the Calvinist College of Marosvásárhely. He was admitted to the 4th class.

On April 10, 1816 Farkas Bolyai asked for the approval of his university friend Carl Friedrich Gauss to send János to him at the university of Göttingen. In his opinion at the universities of Pest and Vienna the level of the mathematical courses was not high enough to seriously evolve the talents of János. In his letter he characterized his son like this: “…as he reached his ninth year he could not even do addition yet. […] I started with Euclid, then he got to know Euler. By now he completely knows the first two volumes of Vega (which I use in my courses), and he is also well versed in the third and fourth volumes. He loves differential and integral calculus, and does them with an extraordinary ability and ease. […] He perceives much and quickly, and he often has highly gifted intellectual glances.” Gauss did not reply to this letter.

At the end of 1816 Farkas thought to send his son to a military officer’s career, and János also agreed with the idea.

On July 30, 1817 János passed his final exam in the Calvinist College of Marosvásárhely as the first of his year.

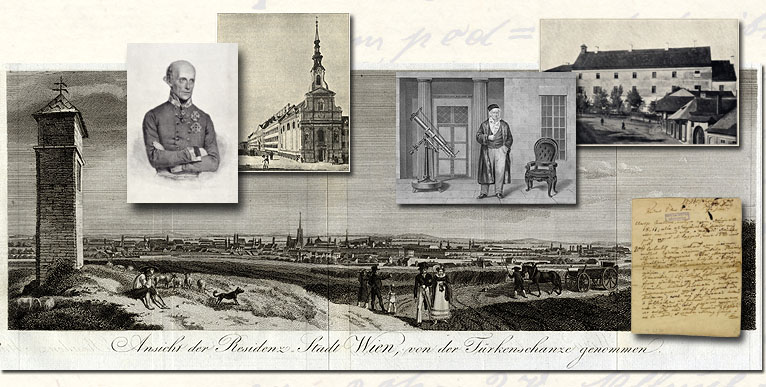

On August 24, 1818 he passed a successful exam of admission at the Imperial and Royal Academy of Engineering, founded in 1717. As the sixth one on the order of results, he was directly passed to the 4th class, the highest level one could reach by exam. (The academic studies embraced eight years, and thus he only had to count with four years of schooling.) His studies were supported among others by Count Miklós Kemény, the main guardian of the College of Marosvásárhely, and Count Ádám Kendeffy.

On August 24, 1818 he passed a successful exam of admission at the Imperial and Royal Academy of Engineering, founded in 1717. As the sixth one on the order of results, he was directly passed to the 4th class, the highest level one could reach by exam. (The academic studies embraced eight years, and thus he only had to count with four years of schooling.) His studies were supported among others by Count Miklós Kemény, the main guardian of the College of Marosvásárhely, and Count Ádám Kendeffy.

Before April 1820, probably in the academic year of 1819–1820 Archduke Johann – the younger brother of Emperor Franz I, and the chief director of the Academy – on an official visit took notice of the mathematical talent of the younger Bolyai, and as the supervisor of the engineering corps he did not forget about him later.

In the spring of 1820 he informed his father about his experiences concerning parallels. Farkas in a long letter warned his son against this: “…don’t go any step further, or else you’re a lost person.”

On September 18, 1821 his mother died.

On September 6, 1822 he completed the last semester of the Academy with excellent certificate, as the second best student of his year. (The order of excellence of the students was established by the professors and the students in common, and although the professors considered János as the best, the vote of the students was decisive.) The two best students, thus also János were kept at the Academy for one more year as “Ingenieur-Corps Cadets” for supplementary studies, especially important for military architects. Their subjects were: the second part of fortification, architecture, plans of fortification and architecture, German writing and French.

On September 1, 1823, after the year of cadetship János was appointed sub-lieutenant and commanded to the directorship of fortification in Temesvár (Timişoara).

On November 3, 1823 he wrote his famous letter to his father, in which he informed him about the discovery of a “new, different world,” that is, the system of the first non-Euclidean geometry:

“My Dear Fater!

I have so hopelessly much to write about my new inventions that I cannot do else than not to write exhaustively about anything, but only write some words of each […]

I already know that as soon as I can, I will publish a work on parallels. It is not completely clear yet, but the way I’m proceeding on almost certainly promises to reach the purpose, if it is possible at all. It is not complete yet, but I found so majestic things that I was astonished myself, and I feel it would be a pity to let it perish. You will also find so yourself, my dear father, when you will see it. Now I cannot say more, just that I have created a new world out of nothing: everything I had sent before was only a house of cards in respect to a tower. I am convinced that it will increase my esteem just as if I had invented something.”

In the first days of February 1825, after six and half years of absence he visited Marosvásárhely again. At this time his father was married again: in the fourth year of his widowship he married Teréz Nagy of Somorja, the daughter of a local merchant.

From April 10, 1826 he began his service as sub-lieutenant at the directorship of fortification of Arad. His direct superior was Johann Wolter von Eckwehr, his former professor of mathematics at the Academy of Engineering, with whom he had been in correspondence. In 1826 János gave over to him his manuscript treatise in which he summarized his researches on non-Euclidean geometry (this manuscript has been lost).

In December 1827 – January 1828 his health turned worse. The report of the directorship of fortification of Arad to the technical office of Vienna included that “Lieutenant János Bolyai asked six weeks of leave to his father in Marosvásárhely because of his convalescence after illness…”

At the end of January 1828 János was already in Marosvásárhely. There he saw for the first time his half-brother Gergely (1826-1890), and he saw the manuals of mathematics of his father prepared for publication: The principles of mathematics (Marosvásárhely, 1830) and Tentamen. (The manuscript of this latter had been prepared by as soon as 1829.) Probably also János presented to his father his German treatise summarizing his results in geometry, and their exchange of views may have inspired János to deepen his research concerning the space of absolute geometry.

Around April 25, 1828 he went back to the place of his service in Arad.

From the second half of 1828 he was often ill, due to contagious malary which caused regular intermittent fever.

In October 1828 he was commanded to go from Arad to Nagyvárad (Oradea) and to complete there the survey of the fortifications by the next military year of 1829.

On the spring of 1829 he made several surveys for the renovation of the fortifications of Szeged and Nagyvárad.

From December 8, 1830 he was appointed the chief engineer of the directorship of fortification of Lemberg (Lvóv), but he occupied his post of service only six months later.

From the beginning of December 1830 until May 1831 he spent his holiday in Marosvásárhely, which was decisive in the preparation of his Appendix, as his father insisted on his putting it on paper.

Some weeks after his departure from Marosvásárhely, on July 13, 1831 his father wrote in a letter to Lajos Jakab on the space theory of János: “It is an original great work that will be appreciated everywhere; no similar work on mathematics has been written by any Hungarian author…”

During this time they decided that the work of János will be included in the first volume of the Tentamen as an Appendix. On the way to his new place of service, in Beszterce (Bistriţa) János was infected with cholera.

On May 15, 1831 he arrived to Lemberg healed, but not completely healthy, and started his service.

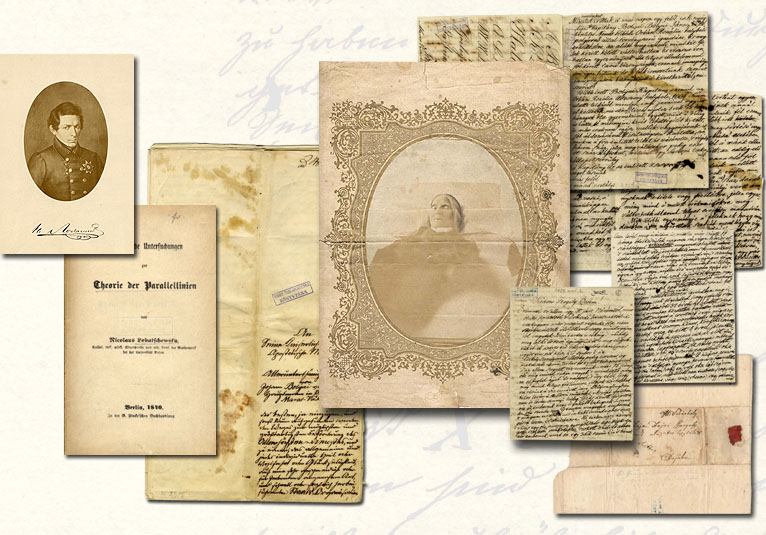

In the middle of July 1831 Farkas Bolyai did not wait until the Appendix can be published together with the Tentamen, but published the treatise of János in a separate small volume.

János had left him 104 forints and 54 kreuzers for the costs of the publication. His father immediately sent a copy of the Appendix by post to Gauss, asking for his opinion, but it was lost on the way.

At the end of October or beginning of November 1831 Lieutenant-Colonel Andreas Zimmer, director of fortification of the army headquarter of Lemberg reported on János Bolyai that he was not able to provide his service, but he recommended to employ him in another post where he can profitably use his expertise in mathematical studies.

On January 16, 1832 Farkas sent the treatise of his son to Gauss again.

On March 6, 1832 Gauss replied that the way János had been following and the results achieved by him coincided with his own research done in the previous 30-35 years and that he himself wanted to compose a similar work but he did not intend to publish it in his own life.

Farkas had made a copy of this letter for his son who received it around April 6, 1832 in Lemberg. This letter unsettled János, and the offence caused by it never passed.

(Nevertheless, Gauss acknowledged in a letter of February 14, 1832 written to Christian Ludwig Gerling that his ideas had not been as mature as those of the young Bolyai, and he also added: “I consider this young geometer, Bolyai, a first-class genie.”)

On March 14, 1832 he was promoted to captain.

From April 27, 1832 to June 15, 1833 he was the officer of engineering of the directorship of fortification of Olmütz (Olomouc).

On May 12, 1832 he left Lemberg for his next station of service, Olmütz.

On May 17, 1832 on the way around Bielitz his waggon fell in a ditch along the road, and he was taken taken senseless to a village near to Bielitz. His wounds and presumable commotion were treated for more than a month. He arrived to his post of service in Olmütz at the beginning of July 1832.

On June 16, 1833 the commission of supervision declared János Bolyai disabled and pensioned him off with yearly 400 forints.

In the summer of 1833 János returned to Marosvásárhely. He lived with his father who at the end of March 1833 became widow for the second time.

In 1833 (or, according to a note of 1834 by János Bolyai, at the end of 1833) was published the second volume of the Tentamen of Farkas Bolyai. The first volume of this work, published in 1832 contained the Appendix by János.

In 1834 the father and son agreed that János would move out to Domáld and manage there the family estate. János lived there twelve years with short breaks.

Since August 1834 he lived with Rozália Orbán of Kibéd, coming from a Calvinist noble family. They had two children: Dénes (1837-1913) and Amália (1840-1893). They could not legally marry, because they could not provide the caution which was necessary because of János’ military officership.

In November 1837 the Prince Jablonowski Scientific Society of Leipzig conducted a competition for the foundation of the theory of imaginary numbers. János sent in his Responsio based on principles similar to those of the complex numbers founded by William Rowan Hamilton.

Although he presented his work in 1837, he laid down his theory already in 1831. Farkas Bolyai and Ferenc Kerekes, the professor of mathematics of the Calvinist College of Debrecen also submitted works to the competition. This latter received half of the first prize. The treatises of the two Bolyais were not prized.

At the beginning of 1841 his improving health and family conditions offered him possibility to the realization of his scholarly ideas. Besides his mathematical research he also decided to write a work embracing the whole human knowledge.

On December 31, 1841 he wrote a letter to Friedrich Hasse, the secretary of the Jablonowski Society, in which he asked back the manuscript of the Responsio.

In 1842 he continued to work on mathematical problems, as it is attested by four letters writte in this year.

On January 27, 1845 the younger brother of Farkas Bolyai, Antal died. After this date Farkas started to control the conditions of the family estate of Domáld managed by his son, and he found that János completely neglected it. Thereafter he withdrew the right of János to live on the estate and he let it out to someone else.

In 1845 János purchased in the Németvárosi street of Marosvásárhely the house number 1004 in the neighborhood of the fortress. As an owner, the mother of his children Rozália was registered.

At the beginning of 1846 János moved with his family from Domáld to Marosvásárhely.

On October 17, 1848 he received of his father the Geometrische Untersuchungen zur Theorie der Parallellinien by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevski. Later he wrote a critical study on it.

On May 18, 1849 János Bolyai and Rozália Orbán married. During this period of the Hungarian war of independence of 1848-1849 Marosvásárhely fell out of the control of the imperial army, so they could pass over the prescriptions obligatory for the imperial officers. After the suppression of the war of independence the military authorities declared the marriage illegal, but it remained valid from civil and ecclesiastical point of view.

On June 15, 1849 was dated a draft of János to the leader of the war of independence, Lajos Kossuth, in which he attempted to convince Kossuth to employ him in his government and support the realization of his ideas for the development of the country.

On July 31, 1852 Emperor Franz Joseph during his Transylvanian tour also visited the Calvinist College of Marosvásárhely. Farkas Bolyai prepared to the event in the name of the staff with a speech and with a poem in three languages, while János prepared a draft in German in which he made various proposals to the emperor about the promotion of the development of the empire.

On November 26, 1852 János Bolyai and Rozália Orbán signed a document of divorce. János obliged himself to leave the house in which they had lived together.

From the end of November 1852 until January 1857 János Bolyai lived in a room rented at a carpenter in Marosvásárhely, in the house number 905 in Kálvária street. In these years his illness worsened.

On November 20, 1856 Farkas Bolyai died.

In January 1857 János Bolyai moved together with his servant Júlia Szőts to the house number 902 in Kálvária street, where four other families lived.

On November 6, 1859 he wrote to his younger brother Gergely that he has been ill and unable to work for fifteen months.

On January 18, 1860 he fell in pneumonia, and not much later in meningitis.

On January 27, 1860 he felt so bad that Júlia Szőts began

to write a letter to Gergely

Bolyai. Before finishing it she checked János once

more, and continued like this:

“While I was writing this letter, he died.”

On January 29, 1860 he was buried in the Calvinist cemetery of Marosvásárhely. Besides the prescribed military accompaniment only Júlia Szőts and three other citizens took part at the funerals.

No authentic portrait of János Bolyai has been left to us. However, it is largely accepted that one of the reliefs on the upper façade of the palace of culture in Marosvásárhely is a true representation of him. This was attested by those knowing him personally, and also by the fact that the relief is similar to his son Dénes. This relief was used as a model for the plaquette representing János Bolyai, created by Kinga Széchenyi on the Bolyai anniversary of 2002.

Literature:

Ács Tibor: Bolyai János új arca – a hadi mérnök. Bp., Akadémiai K., 2004.

Benkő Samu: Bolyai János vallomásai. Bp., Mundus, 2002.

Dávid Lajos: A két Bolyai élete és munkássága. 2. bővített kiadás. Bp., Gondolat, 1979.

Kiss Elemér: Matematikai kincsek Bolyai János kéziratos hagyatékából. 2. bővített kiadás. Bp., Typotex, 2005.

Prékopa András: Bolyai János forradalma. 1. rész, Természet Világa, 133. évf. 7. sz. 2002. július; 2. rész, 133. évfolyam, 8. szám, 2002. augusztus; 3. rész, 133. évfolyam, 9. szám, 2002. szeptember

Szénássy Barna: Bolyai János. Bp., Akadémiai K., 1978.